How We Win Again: Accountability, Organizing, and the Needed Democratic Mobilization

Contributor: Ned Howey

Across Europe, mass mobilizations have emerged in response to the far right’s growing power. In the United States, we’re beginning to see renewed energy in reaction to Trump’s actions dismantling democracy before our eyes.

But parties on the left—particularly the Democrats in the U.S.—would be mistaken to assume this energy automatically translates into future electoral support. While disapproval of Trump has surged, Democratic approval has dropped to one of the lowest points in recent history. That’s not just an inconvenient polling figure—it’s an apparent political contradiction we need to take seriously. But its underlying logic as felt by constituents is clear: the expectation of opposition political parties is not just to be better than the horrific parties they oppose but to effectively produce results that will win power and make the change required.

There is widespread anger at Trump, but no widespread belief in the Democratic Party as the vehicle to stop him. That fact should be central to any conversation about how we move forward.

The Harris campaign’s failure to generate hope was not just a messaging issue—it was symptomatic of a broader collapse in belief that the Democratic Party can deliver anything beyond damage control. As I wrote in The Unwinnable Uphill:

“At some point, the chickens will come home to roost on a politics that is just built off of fear of not taking action rather than the promise of possibility in taking action. Democracy is built off of an unwritten understanding that our participation in it will be rewarded with better outcomes for our shared future. Without that, democracy decays even if the written rules remain. At some point, we need hope and vision to pull us out from our exhaustion.”

Instead, what voters were given was another round of fear appeals in the form of speaking to how Trump would attack democracy itself. While true - the assumption that this itself would mobilize forces for a win fell short.

As I wrote in On the Paradox of Democracy, Transformation, and Accepting the Darkness Ahead, the problem runs deeper than any single campaign or leader: “Fear over the alternative can have a role, but cannot stand alone as a strategy over time… Without hope, participation becomes a burden rather than a possibility. Democracy begins to hollow out—not through a coup or the repeal of voting rights, but through the simple erosion of belief that it can produce anything better.”

The Harris campaign, like many before it, fell into the same strategic trap—focusing on the threat of the alternative, rather than providing a compelling vision of the future. When asked on national television how her presidency would differ from Biden’s, Harris offered no meaningful distinction. And with that, the last thin hope for a transformational shift collapsed into a tired echo of the status quo.

This isn't just about Harris. It’s about the broader failure of political institutions to meet people in a place of possibility, to ask them not only what they’re afraid of, but what kind of world they want to build. The same applies to Europe - it's a lot easier to agree on who to hate than to rally deep support for an agreed solution. But how do we react to fix our own issues when those in power and their actions are all encompassing?

One of the most telling signs of political disconnection today is how differently voters relate to the parties they support—or once supported. I’ve noticed that on the US Right, Republicans are often spoken of by their base as “ours.” - even when they complain about it. Despite deep contradictions and elite-serving policies, the party is perceived as a reflection of its supporters. There’s ownership. On the Left, it’s the opposite. Democrats are spoken about in the third person. Even among their own base, they are referred to as “they,” not “we.” Something external and beyond their control. Until this changes, there will be no winning again.

That simple linguistic difference speaks volumes about the current crisis. As long as Democratic voters see the party as external to themselves—something to vote for, or against, or hold their nose and tolerate—it will never generate the level of engagement needed to win meaningfully or govern effectively.

Political parties cannot survive—let alone transform—if they are perceived as separate from the people they seek to represent. The energy of movements cannot flow into a vessel that is viewed as broken or belonging to someone else. And yet, this is the status quo. Here constituents are expected to serve the party: to volunteer, donate, vote. But they are not treated as agents of change within it. There is no clear mechanism by which participation leads to influence, let alone transformation.

In The Age of Junk Politics, I described this dynamic as one where political structures have inverted the relationship between power and people:

“Our transactional paradigm fails us because it’s assumed we can keep winning through surface level change of ‘targets’... who are actually constituents…[and who] at one time were considered the agents of democracy rather than the targets of it.”

This inversion has consequences. It breeds cynicism. It fosters detachment. And it erodes the very sense of ownership and agency that democratic systems depend on.

Until we reverse this logic—until we reestablish a politics where parties serve constituents and not the other way around—there is no campaign strategy, no amount of messaging, no new candidate that can fix what’s broken.

This is not just a matter of political marketing or optics. The crisis we’re facing is structural. Rebuilding democratic power requires more than just mobilizing against the threat of the Right—it requires constructing a new relationship between people and politics. That relationship must be rooted in three things: accountability, hope, and agency.

Accountability means that parties and political leaders are answerable to the people—not just at election time, but in how they govern, how they make decisions, and how they reflect the values of those they claim to represent. This requires more than listening tours or performative consultations. It means shifting the locus of power back to the people themselves. Not just hearing feedback—but acting on it. Not just outreach—but transformation. Constituents shouldn’t be expected to give loyalty to political institutions that show none in return.

Hope is more than emotion—it’s a political necessity. Without a sense of forward possibility, people disengage. They stop showing up. They protect what little they have and assume nothing better is coming. Hope is not naïve. It is strategic. As I wrote in The Unwinnable Uphill, democracy depends on the belief that participation will result in better outcomes. If people stop believing that, democracy itself withers—regardless of whether elections continue.

Agency is the antidote to the passivity cultivated by transactional campaigning. It’s what people feel when they believe their actions matter. And that feeling only comes when participation is linked to meaningful outcomes—not just symbolic gestures or last-minute pleas to "get out the vote." When constituents feel no agency, even mobilization becomes hollow. They may show up in moments of emergency, but they won’t stay. They won’t lead. They won’t rebuild the systems that need rebuilding.

These three pillars—accountability, hope, and agency—aren’t abstract values. They are the conditions required for a democratic revival. And there is a way to build this even in times of crisis, even when political parties have lost trust.

The solution to this is found in mobilizing and organizing.

You can understand your constituents’ standing on issues, policy, or candidates through polling. You can understand your constituents’ language and way of thinking about issues through focus groups. Only with organizing can you understand your constituents’ values. Which is the key to leadership.

This is the distinction too many political strategists—and parties themselves—fail to grasp. Polling and focus groups are useful tools, but they are diagnostic. They tell you where people are. Organizing is different. Organizing is relational. It is dynamic and links you to your constituents beyond the moment. It reveals what people care about at a core level—and it allows them to shape the future alongside you.

Traditional politics relies heavily on transactional approaches: messaging, persuasion tactics, and last-minute fundraising appeals. These might generate short-term movement, but they don't build trust, and they certainly don't build power. In fact, they often backfire. Every message that treats a supporter like a target, rather than a participant, reinforces the disconnection people already feel.

Even when done with the best of intentions, these approaches have become so optimized for outcomes that they’ve forgotten the process. And that process—of connecting, listening, building—is what actually creates the conditions for change.

People are exhausted not just because the stakes are high, but because the avenues available to them feel hollow. They’re being asked to care, to donate, to show up—without ever being asked what they want to build. And in the absence of that invitation, people are increasingly taking their chances on the unknown. That’s not irrational. That’s what people do when they’ve been failed by institutions too many times.

Organizing is something else entirely. It’s about relationships, not reach. It’s about values, not just voter files. It’s the only way to rebuild the trust and depth that politics today lacks.

We don’t need to manage expectations anymore. We need to raise them.

And we can’t keep treating organizing as something campaigns do when they have extra time. It is the only path forward if we want a politics rooted in anything deeper than opposition.

Organizing and mobilizing aren’t abstract values or long-term ideals. They’re pragmatic solutions to the immediate crisis of trust, participation, and political disaffection. Even in the worst of times—when faith in institutions is at its lowest—people still want to be part of shaping something better. But they have to be asked. Not asked to give, or vote, or volunteer. Asked how they want their party to change. How it can win. What future they’re willing to fight for.

When done well, mobilizing and organizing aren’t just a way to reach people like broadcast messaging tactics—it’s a way for people to actually connect. That’s its power. It builds trust through direct, human-to-human conversation. It opens the door for shared meaning, not just alignment on a policy or talking point. And when people are the ones mobilizing—not just being mobilized—that’s when real political culture begins to shift.

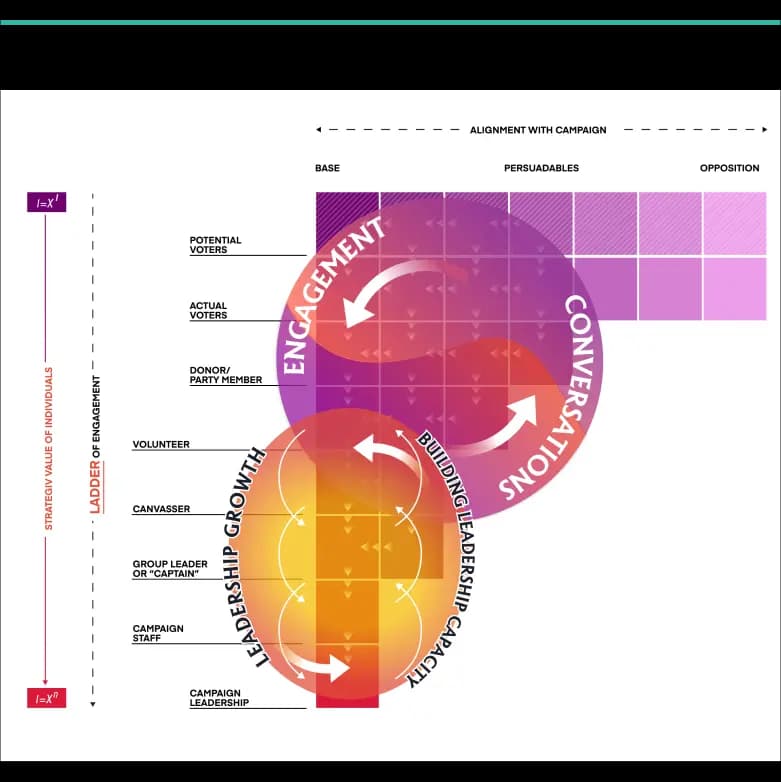

In The Age of Junk Politics, I laid out the Transformation Model—a practical framework for rebuilding democratic politics through meaningful participation. At its core, the model identifies four interlinked dimensions that allow political campaigns to move beyond transaction and toward transformation:

Depth of action: Campaigns often rely on shallow asks—clicks, shares, donations. But deeper forms of action—like initiating conversations, facilitating community discussions, or leading organizing teams—create meaning. They signal trust, and they demand commitment. People feel invested because they are doing something that matters.

Depth of participation: Tokenistic listening won’t solve a crisis of trust. Participation means actually shaping strategy, direction, and decisions. This requires moving power—not just symbolically, but structurally—toward those doing the work.

Depth of leadership: Campaigns that rely on one central figure miss the opportunity to build distributed power. When leadership is nurtured in others—especially those historically excluded from power—movements grow stronger, faster, and deeper.

Relational over transactional: Politics that only asks what someone believes misses why they believe it, and how that belief connects to others. Relational approaches make space for transformation—where beliefs can evolve, solidarity can grow, and organizing becomes an act of collective meaning-making.

Campaigns too often focus only on those already aligned and already taking action. But building lasting power means working across two axes: increasing alignment and increasing engagement. That means meeting people where they are—whether they’re just potential voters or already leaders—and moving them up the ladder of involvement: from awareness, to participation, to ownership.

This isn’t a straight line. It happens through conversation, where people are listened to, supported, and the relationship developed. It happens through leadership growth, where canvassers become team leads, and team leads become organizers, and so on. And it happens through building capacity, where every layer of engagement is structured to create more organizers—not just more contacts.

Technology should not be the center of this, but can help support the work. Mobilizing tools (like Qomon, who sponsored our most recent newsletter) now make it possible to scale this feedback loop. Instead of just logging outreach, they help campaigns listen—gathering insights about what people care about. When integrated with organizing for deeper engagement, these tools help turn digital interactions into participatory action.

Another key strategy is distributed organizing—empowering supporters to take on leadership and drive outreach themselves. As outlined in The Definitive Guide to Distributed Organizing, this approach isn’t just efficient—it’s relational. It enables deeper reach and more authentic connection, because the messengers are the community.

We’re seeing early examples of this work already. In Belgium, the Parti Socialiste’s Sans Tabou campaign chose to lead with humility. Instead of assuming what their base wanted, they asked—publicly, openly, and in person.

None of this is easy. It requires shifting resources, rethinking goals, and accepting that control needs to be shared. But the reward is more than just better engagement—it’s the foundation for rebuilding trust, growing leadership, and reclaiming a sense of democratic possibility.

This is the revolution of participation needed. And it is time to begin.